Conquering planet Earth – Duran Duran in the 80s

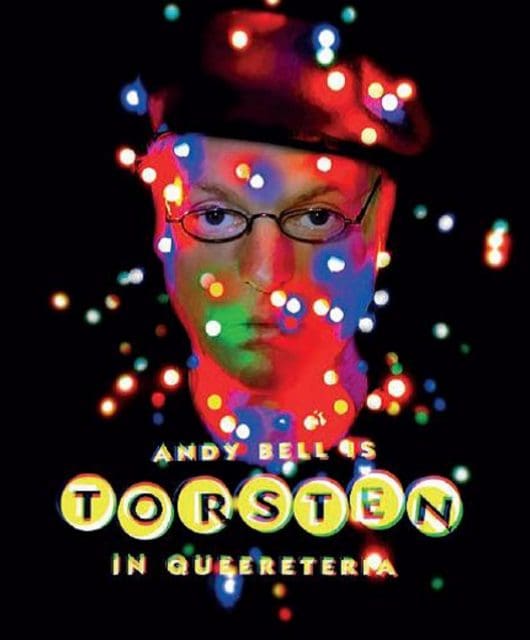

By Mark Lindores | May 16, 2022

From dingy pub back rooms to tropical climes, the glamour and excess of the Duran Duran success story defined the 80s. However, becoming the biggest band in the world came with a hefty price tag…

As the dying embers of punk gave birth to a new wave of flamboyantly-dressed club kids who pouted, preened and posed a trail across London’s West End in the late 70s, 100 miles away, a Birmingham five-piece with killer hooks to match their looks were honing a sound that would not only make them one of the defining acts of that stylish subculture but would also give the New Romantics their name.

The brainchild of Nick Rhodes, John Taylor and Stephen Duffy, three friends who shared an obsession with David Bowie, Roxy Music and the Sex Pistols, the group was born of a fervent desire to eschew the monotony of a life mapped out in the grey, grim setting of industry and manual labour, choosing instead to embark on the infinitely riskier yet glamorously glitter-strewn trail blazed by their musical heroes.

Inspired by their idols’ own escape from the mundane and the everyday by transforming themselves into otherworldly beings, the trio decided that forming a band would be their passport to superstardom.

“None of us even knew how to play an instrument at that time,” Nick Rhodes later recalled to the BBC. “But we knew that was just something we would have to learn, an obstacle that was getting in the way of what we really wanted to do – which was being in a band somehow.”

Read more: Top 40 Duran Duran tracks – year by year

Duran Duran: Making The Wedding Album

Roles within the group would change sporadically as new members joined and quit, but the original line-up revolved around Stephen Duffy as singer and lyricist (plus occasional bass and drums), Simon Colley on bass, John Taylor on guitar (he moved on to bass after Colley left), and Nick Rhodes playing the synthesiser. In this format, the group began cultivating a unique sound which com prised elements of all the artists they loved.

Realising their four-man line-up placed limitations on the kind of music they could make, they recruited drummer Roger Taylor (a previous acquaintance from the Birmingham music scene) and guitarist Andy Taylor via an advert in the Melody Maker.

Now fully staffed, and having named themselves after a character in Jane Fonda’s campy, sci-fi sex romp Barbarella, the newly-christened Duran Duran were intent on putting Birmingham on the musical map, bridging the gap between the scintillating synth-pop that was defining London’s club scene and the punky new wave of Manchester.

The key to the group transcending the back rooms of Birmingham pubs came with their installation as house band at the Rum Runner, the city’s portal for emerging music trends. The venue was often described as the city’s own version of London’s Blitz club, although owners Paul and Michael Berrow had, in fact, taken their inspiration from the iconic nightspots of New York.

They would frequently visit the Big Apple to check in on what the latest clubs were doing, returning with suitcases filled with the hottest Stateside records, often giving them the upper hand over Steve Strange’s operation in the capital.

“It was much edgier in Birmingham,” Nick insists. “When we came to London we finally went to the Blitz and we thought, ‘Is this it?’ because it was all so manicured and nice. Birmingham was more real and less cliquey – the crowd there was very colourful, fun and expressive. It was like fantasy world, really. If you made a Hollywood movie and they tried to cast it, however quirky they tried to make it, it would never touch what it really was.

Read more: Making Seven And The Ragged Tiger

Read our feature on Duran’s 1990 album Liberty

“Paul and Michael Berrow had gone to New York to Studio 54 and Paradise Garage, and came back with a vision to bring that to Birmingham. And the look of the Rum Runner, with the mirror tiles and the neon, was a big part of that.”

The Berrows had been impressed by the demo tape Duran Duran had given them to land a gig at the club and, spotting the new outfit’s obvious potential, decided to take on a much more significant role, offering to manage the band on a full-time basis. As the brothers boasted a bulging contacts book and had a single-minded ambition that matched that of the band themselves, it made for a perfect union.

As well as managing the group, the Berrows allowed them to use the club as rehearsal rooms when it was closed (as they did with UB40 and Dexys Midnight Runners), gave them jobs as barmen, glass collectors, doormen and DJs, and bought them instruments and equipment.

However, just as the group felt they were on the verge of a major breakthrough, they were dealt a severe blow when Stephen Duffy quit to form his own band, The Hawks, deciding he didn’t want the fame and adulation the outfit was obviously headed for. The move threw Duran Duran into turmoil as they suddenly found themselves without a lead singer and lyricist.

In May 1980, after a succession of new vocalists including Andy Wickett had failed to work out (“We were known as the band that had a different singer at every gig” Nick says), Fiona Kemp, a barmaid at the Rum Runner, recommended they should meet her boyfriend, who had sung in various punk bands around town.

With a background in musical theatre, Simon Le Bon had been a minor child star and was studying drama at Birmingham University when the opportunity to join the band came along. For his audition, he perhaps ill-advisedly went in character as a “rock star”.

“I turned up in a pair of pink, skin-tight, washed-out, leopard-skin trousers,” Simon recalls. “I just put on the best clothes I had that I thought would appeal to a band – especially as Duran Duran had previously, I’d heard, had a very stylish lead singer.”

Sartorial misstep aside, Duran Duran and Le Bon were the perfect match, not only as band and frontman, but also from a songwriting perspective. The group had proved they knew how to create catchy, groove-based melodies, but were struggling in the lyrical department since the departure of Duffy. Le Bon arrived with a notebook crammed with poems and song lyrics he had written.

“Not only were they lyrics, they were really great lyrics,” Nick Rhodes said. “I remember looking through them and thinking ‘Wow! These are songs in here. All we have to do is write music to these.’”

With their line-up complete, the band quickly threw themselves into writing and recording, supporting themselves with their jobs at the Rum Runner while playing regular gigs at the club. As the house band, they quickly established a loyal, sizeable following, with crowds flocking to see them.

Ambitiously wanting to create a kind of multimedia event, Duran Duran took their cues from the art-rock of The Velvet Underground, incorporating film projection, theatrical costumes and references to the Warhol scene and the dark decadence of the Berlin cabaret circuit into their live shows.

As their appeal grew, the Berrows sensed that the band had reached its zenith within Birmingham and decided to boost their visibility by getting them booked onto Hazel O’Connor’s Breaking Glass Tour of the UK as the support act.

As the band attracted praise from critics up and down the country, a bidding war among record companies broke out, with representatives from all the major labels descending on the concluding show of the tour in London in December 1980. Phonogram and EMI emerged as frontrunners and the boys opted for the latter, citing “a certain patriotism” to The Beatles as their reason for doing so.

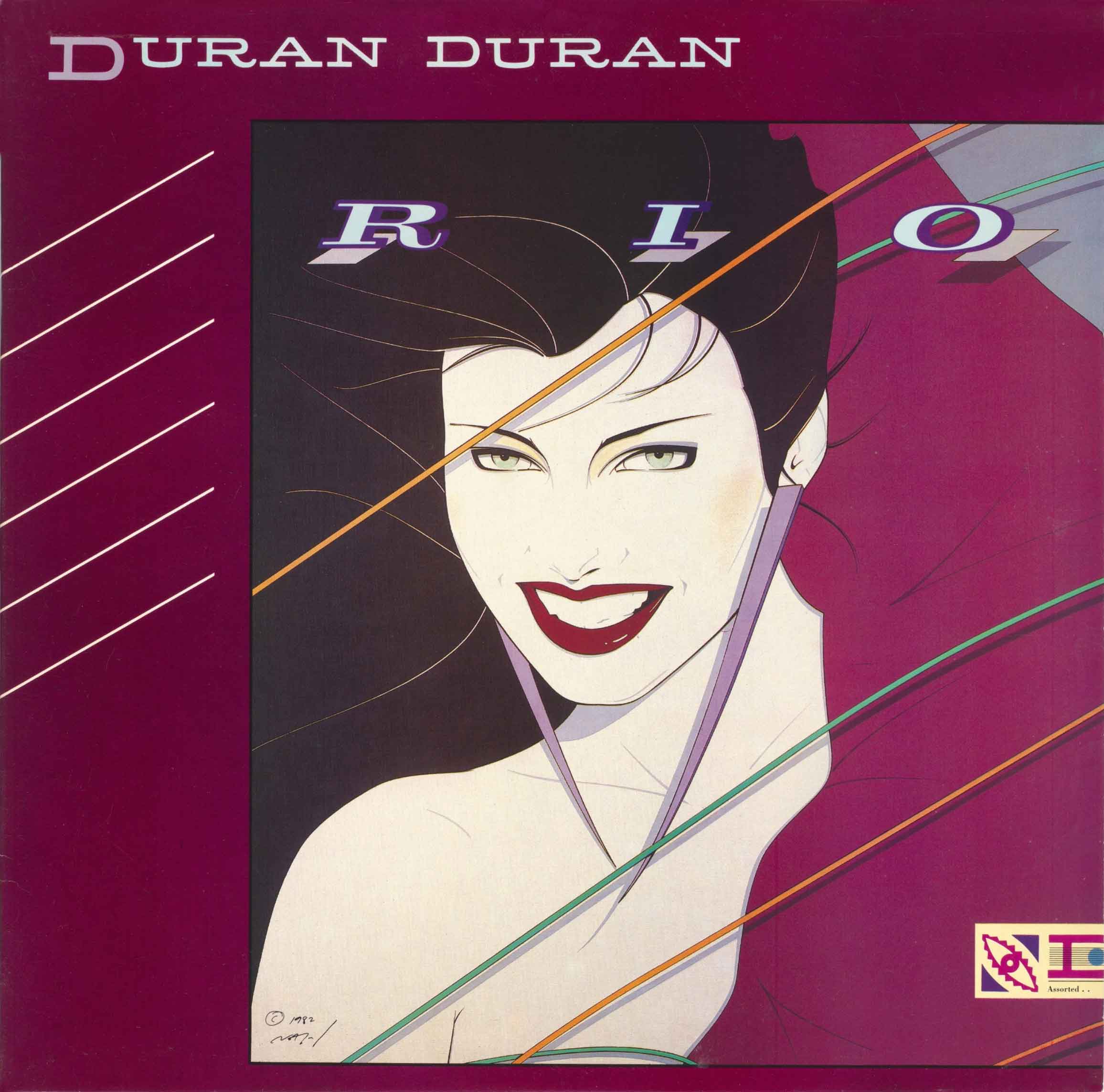

Duran Duran: Making Rio

Read more: Making Duran Duran’s Notorious

Having inked their first record deal, the band were keen to deliver on the first requirement of that contract and headed straight into the studio to begin work on their debut album.

Thrilled to find themselves alongside Colin Thurston, who had worked on some of their favourite records, such as Bowie’s “Heroes” and Iggy Pop’s Lust For Life, Duran Duran’s implicit trust in their producer ensured that the recording sessions ran smoothly and quickly, and they completed the whole record in a matter of weeks.

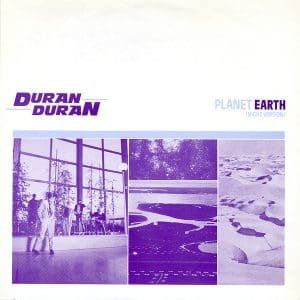

The debut single, Planet Earth, was released in February 1981. Fulfilling their manifesto of fusing disco, punk, new-wave and synth-pop, the track acted as an ideal four-minute teaser of the Duran sound. As well as landing them a coveted spot on Top Of The Pops and reaching No.12 in the singles chart, it crossed over to clubland, becoming a huge dance hit.

Thanks to its “Like some New Romantic looking for the TV sound” line, the band was embraced by the subculture that was referenced in the lyrics.

However, after the follow-up single Careless Memories barely scraped into the Top 40, the Berrows decided to implement a strategy they had come up with during a trip to the US, where they had witnessed the increasing importance of music videos.

Played on giant screens in clubs such as New York’s Danceteria and on video jukeboxes, visual promos were becoming such an integral aspect of the music business that a 24-hour music TV channel was due to be launched. Rightly sensing that the medium of video would be a highly effective marketing tool for a group of five attractive guys, the Berrows – and the band – embraced the concept enthusiastically.

After the basic ‘studio performance’ videos for the first two singles, the sexually-charged Girls On Film video, with its gratuitous shots of semi-naked models mud-wrestling, pillow-fighting and running ice cubes over each other’s nipples was a masterstroke in the art of turning controversy into currency, hitting the headlines and earning the band priceless publicity.

It was the most requested clip on video jukeboxes for three years running, and a censored version became one of MTV’s most-played promos, while the single also benefited from the video’s notoriety, becoming their first to reach the UK Top 10.

With two big hits under their belts and a burgeoning teenage following, Duran Duran’s eponymous debut album was released in June 1981, reaching No.3 – the beginning of a run in the Top 100 that would last more than two years. With the album presiding in the upper reaches of the chart while the band toured in the summer of 1981, they were already keen to get to work on their next long-playing collection.

They had the majority of the songs written (Rio, Save A Prayer and The Chauffeur were among the lyrics Simon Le Bon had brought to the band in his infamous notebook). This material promised a huge progression from the debut album, and all five members wanted to get them recorded as quickly as possible.

By 1982, the New Romantics were on their way to being regarded as old news. Aware that being considered part of a scene limited them, Duran were keen to distance themselves from it.

By 1982, the New Romantics were on their way to being regarded as old news. Aware that being considered part of a scene limited them, Duran were keen to distance themselves from it.

If their debut had been the band getting its foot in the door of the pop world, Rio would see them kicking it off its hinges. A big, brash pop album, expansive in both scope and sound, it displayed a band that were ready to take on the world.

Although songcraft was fundamental to the album’s success, a forward-thinking approach to its rollout was key. After realising the power of video with Girls On Film, the Berrows sent the boys to Sri Lanka and Antigua to film the videos for the album to enhance the jet-setting playboy image the band were cultivating.

The simpatico relationship between their music and visuals became an integral part of the success of the group, with their cinematic clips becoming MTV mainstays.

Duran Duran: Making The Wedding Album

Read our feature on Duran’s cover art

As they lived it up on camera in exotic climes, the Rio videos also helped establish their fanbase. While Girls On Film had drawn criticism for its objectification of women, they redressed the balance by objectifying themselves in turn with countless scenes of the guys languishing shirtless on foreign beaches. These pop heart-throbs looked like perfect fodder for the likes of Smash Hits, No.1 and Look-In.

While mainstream success had always been Duran Duran’s ultimate goal, the rapidity at which that success turned to mania took everyone by surprise. As Rio’s delayed success in the US took hold in 1983, the band found itself the lynchpin of a second ‘British Invasion’, leading the charge of acts such as Culture Club, Eurythmics, The Police and Bananarama.

Dubbed “The Fab Five” in reference to the moniker given to John, Paul, George and Ringo two decades earlier, the hysteria that surrounded every concert, TV appearance or record shop signing (12,000 fans flocked to New York’s Times Square to meet them in 1983) was unlike anything seen since Beatlemania.

As the adulation began to impact upon their private lives, they began to feel like prisoners of their success, unable to go out without being mobbed. As fans craved more and more contact with the band, nothing seemed off limits.

In the age of social media, artists can post an Instagram story or tweet to appease the constant need for updates; in the 80s, every weekly magazine feature and television interview was pounced upon and eagerly devoured, and soon fans began to follow the band everywhere and even hold vigils outside their homes.

The constant pressure and scrutiny soon took its toll on some members of the band, particularly Roger, Andy and John. As the biggest pin-up, John particularly struggled to cope, throwing himself into the debauched rock star lifestyle.

“All I knew was that The Beatles did drugs, the Stones did drugs, The Clash did drugs… why would you not want to do them?” he later revealed to VH1. “If someone is really attractive and wants to have sex with you, then why not?”

The band had enjoyed such lucrative success in the Rio era that in early 1983 the decision was made that they should become tax exiles, living abroad for a year. This, it was thought, might also provide respite from the hysteria that surrounded them, as well as minimising the risk of becoming overexposed – something which was a serious possibility at the time, with negative or disparaging articles about the band appearing more frequently in the press.

Read more: Duran Duran Future Past interview

Read more: Stephen Duffy interview

A standalone single, Is There Something I Should Know? was released in March to satiate fans’ appetites for fresh Duran until the next album could be made. It gave the band their first UK No.1 single (it was, in a way, Nick Rhodes’ second, as he had co-produced Too Shy for Kajagoogoo, which hit the top spot in January). Then, in May, Duran departed for Cannes to begin working on their third record.

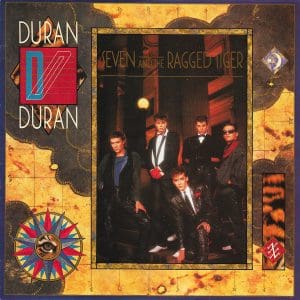

Released in November 1983, Seven And The Ragged Tiger was the result of eight months in France, Montserrat and Australia and cost a reported half a million pounds. As well as revealing a more dance-oriented sound, the group was keen to downplay their image as globe-trotting playboys, fearing it was fuelling resentment towards them.

Released in November 1983, Seven And The Ragged Tiger was the result of eight months in France, Montserrat and Australia and cost a reported half a million pounds. As well as revealing a more dance-oriented sound, the group was keen to downplay their image as globe-trotting playboys, fearing it was fuelling resentment towards them.

“A lot of what was said or written about us at that time was a very big misconception,” Nick later clarified. “It is fair to say that we did play up to the playboy image at the beginning but when people saw us flying all round the world, the truth was we were slaving away in recording studios, playing gigs or shooting videos…

“We just chose nicer places than other people to do those things in. A lot of the time, we only saw the inside of our hotel rooms.”

Although the first two singles had been hits, they had failed to live up to Duran Duran’s impossibly high expectations. It was a radically remixed version of The Reflex, reworked by Nile Rodgers using the very latest studio trickery, that became the biggest hit of the album and also their career, topping the charts on both sides of the Atlantic. Though EMI had initially hated the remix, the band fought for it, feeling it was emblematic of the sound they wanted to pursue.

However, as the tour wrapped in April 1984, none of the band were keen on the concept of going straight back into the studio. After being away for a year, first recording the album then going out on tour, the idea of spending time at home with family and their partners was more appealing than a return to work, however lucrative.

In place of a new album, Duran Duran launched a host of new products including a live video, a backstage documentary of their tour and a photo book capturing them both onstage and behind the scenes.

Released in time for Christmas 1984, Arena was a compilation of live performances from their Sing Blue Silver Tour. As well as live versions of some of their best-known tracks, it also featured a new offering, The Wild Boys. This was intended to be the theme to a proposed film adaptation of William Burroughs’ novel of the same name.

The festive season in 1984 also saw all five of Duran Duran featuring prominently on one of the most important singles of all time – Band Aid’s Do They Know It’s Christmas?

Simon was the fourth vocalist who appears on the song, sharing the microphone with Sting at one point while Roger, Nick, John and Andy contribute to the group vocal. The latter two members also featured as instrumentalists on the track.

Simon claims he was the first person approached by Bob Geldof to get onboard the project. The Duran star readily agreed: “It was this opportunity to do something that wasn’t about ‘me.’ It made you feel you could do something useful.”

At first, Simon was under the impression that he would be singing the song as a duet with Sting. It was only when he arrived at Sarm Studios he realised he’d only be one part of a much bigger picture. He told Rolling Stone magazine: “I thought I was going to get half the song. I was a bit pissed off, because when I walked into [Sarm], they’re already recording somebody else singing one of my lines! That took a while to sort of get my head around.”

After spending five years inside the high pressure cooker of Duran Duran, the band decided to take a break to pursue other musical outlets. John and Andy formed The Power Station with singer Robert Palmer and Chic drummer Tony Thompson (Chic bassist Bernard Edwards also dropped in on production), while Nick, Roger and Simon formed Arcadia.

On top of all this, John released a solo single from the 9½ Weeks soundtrack, Simon cheated death during a sailing competition before marrying model Yasmin Parvaneh, and Andy began work on a solo record.

Following their close association with the Band Aid project, Duran Duran briefly reconvened to perform at Live Aid in Philadelphia on 13 July 1985 – the band were currently at No.1 in the US Billboard chart with their Bond theme A View To A Kill.

Although it was not intended to be a farewell performance, it eventually became the final time that the original fivepiece played live until July 2003.

The band performed a four-song set that comprised current single A View To A Kill, Union Of The Snake, Save A Prayer and The Reflex.

Unfortunately, their Live Aid set became infamous for Le Bon inadvertently hitting an off-key falsetto note in the chorus of A View to a Kill, an error that made headlines as ‘The Bum Note Heard Round the World’. Le Bon later described the moment as the most embarrassing of his career.

Like the hastily-reconvened Led Zeppelin, the band were lambasted in the press with Le Bon being singled out for harsh criticism for that single vocal misstep.

Following Live Aid, band discussions about their next album revealed that not everyone wanted the same thing. Roger Taylor left the group and the music business, and, after weeks of noncommittal discussion, Andy Taylor vanished to pursue a solo career and the band split from Paul and Michael Berrow to manage themselves instead. With Nick, John and Simon pledging to carry on as a trio, the new Duran was to be an entirely different entity.

The sessions for the next album proved problematic. As well as being sidetracked by acrimony and legal disputes with Andy Taylor, the introduction of fresh musicians meant the group struggled to find a new sense of identity. Still, with new guitarist Warren Cuccurullo and producer Nile Rodgers acting as session musicians, Notorious was completed and released in November 1986.

While the title track was a sizable hit, its follow-ups only made a minor impact and the album peaked at an unjust No.16 in the UK, indicating that the streamlined Duran Duran weren’t packing as much punch as before.

As the decade that they had defined drew to a close and music shifted more towards dance culture, the unrest within the band was evident.

“Being in Duran Duran in the late 80s was awful,” John later admitted. “The early days were great, but in the later years we were managing ourselves and people were suggesting that we were finished and should end the band. I was literally hanging on by a thread.”

Though their next album, 1988’s Big Thing, possessed an experimental edge and flirted briefly with the rising club scene, the juxtaposition of that influence with songs that harked back to their earlier work resulted in a rather disjointed collection.

A victim of a band who had seemingly lost their confidence within the evolving musical landscape, Big Thing was a moderate success but clearly indicated there was a need to regroup, establish a direction and redefine their identity as they moved into the 90s.

Buying themselves time and marking the end of their first tenure with the appropriately-titled greatest hits album Decade, they closed an incredible first chapter of the Duran Duran story.

For more info on Duran Duran check out their official website here