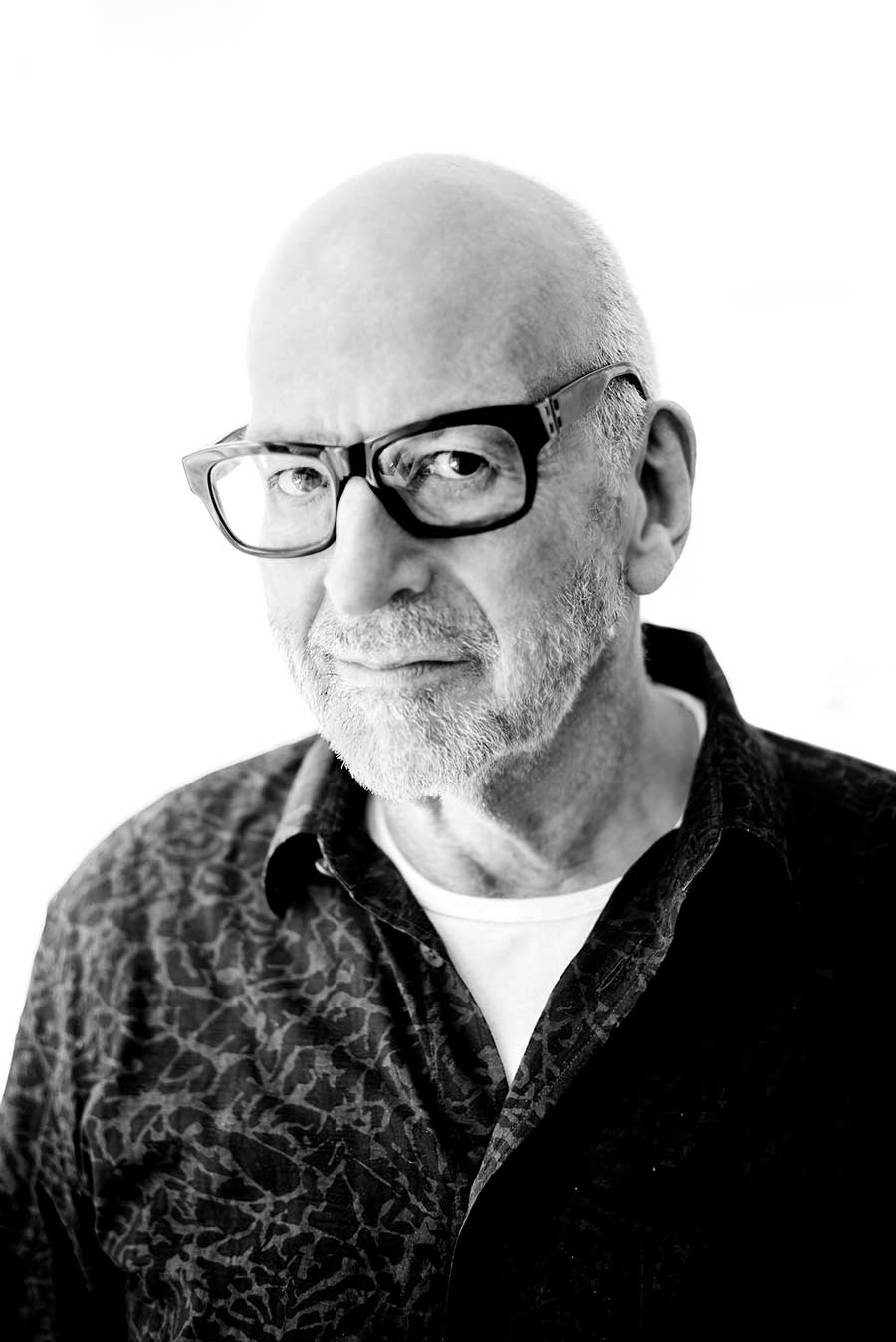

Mute Records’ Daniel Miller talks Vince Clarke

By Andy Jones | September 24, 2022

The story of Daniel Miller and Vince Clarke goes back 40 years. In this interview from 2020, the Mute Records founder candidly looks back over four decades with “A warm-hearted, brilliant musician and songwriter”… By Andy Jones

From the moment Daniel Miller saw Vince Clarke playing with Depeche Mode in 1980, he knew that this bunch of ‘Woolworths New Romantics’ were what his heart and gut had been searching for.

Yet he could never have predicted that he’d still be talking about new albums (and the latest synth trends) with Clarke almost exactly 40 years later.

“I can’t believe I’m talking to a 60-year-old and he probably can’t believe he’s talking to a 69-year-old!” Miller laughs late-on in an hour of reminiscing.

During our chat he digs deep into his own memories for his side of the Vince story, talking graciously about a man who has tasted so much success, and with whom he has shared so many of those major moments: from that first gig to Vince reconnecting with Martin Gore so many years later.

And it all starts with Daniel’s first meeting with Vince when he – according to Vince, anyway – rejected the Mode’s very first demo…

“Well, actually, that’s half true,” Daniel Miller smiles. “It’s not an urban myth, it’s an urban truth! I was at Rough Trade – I used to work out of the shop as a base. We were getting the first Fad Gadget album together and there’d been a problem at the pressing plant.

“I remember walking into the office, or actually I don’t remember – I only remember it because they keep reminding me of it! Vince was there, maybe Dave… not the whole band, as Fletch and Martin were working.

“They were talking to [legendary publicist] Scott Piering, and he said, ‘Daniel, I think you’ll be interested in their demo.’ But I was like, ‘Sorry, I’ve got to go and sort this f***ing problem out!’ That’s my memory of it. It wasn’t like I heard the demo and rejected it.”

What is certain is the impact that Depeche made on Daniel when he eventually went to see them play.

“It was around October 1980 at The Bridge House in Canning Town where they were supporting Fad Gadget,” he recalls with greater ease. “There are three things when you sign an artist: gut, heart and head. It starts with the gut: they were young and made incredible pop music.

“They started and I thought ‘Wow, this is amazing.’ They were these kids, basically, with synthesizers perched on beer crates, and the singer who had under-lighting to make him look ‘gothy’ and completely standing still. I thought ‘Well, that’s a good song…’ and then there were just more and more amazing songs.

“I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. And considering they had very simple synths and a drum machine, the songs were perfectly structured and arranged. They looked pretty too, like – and I’m sure they won’t mind me saying this – Woolworths New Romantics! They made a vague attempt just when the New Romantic thing was getting going. But I thought ‘This is great!’”

Miller continues: “The ‘heart’ part was that this was what I was hoping for in music: a band, all in their teens, all deciding to go electronic and writing amazing pop songs. I had kind of conceived of the idea beforehand with the Silicon Teens which was really a spoof band called ‘the world’s first all-electronic teenage pop group’.

“It wasn’t like they were the new Silicon Teens, but I thought it was revolutionary. I knew in my heart that this was going to happen, but it could have happened and they were shit; instead it happened and they were amazing.”

- Read more: Top 40 Vince Clarke songs

Daniel introduced himself to the band and went to see them play again the following week, “as I almost couldn’t believe what I’d seen. That just confirmed my original thoughts, so I said: ‘Do you fancy doing a single?’, and they said ‘Yeah okay.’ I thought, ‘I really want to do this, not just do it because I like the music but to fulfil their potential.’”

Depeche Mode quickly took off, with plugger Neil Ferris playing a major part in getting them across national radio and helping their first single, Dreaming Of Me, hit the lower reaches of the charts; “and it sold well,” says Daniel.

With Radio One DJs Peter Powell and John Peel getting behind them, second single New Life charted properly. A major four-decade (and counting) career began while the major labels gathered…

“This ball started rolling and the majors got interested,” Daniel remembers. “I didn’t want to hold them back, but at the same time I really wanted to try and do it myself. The majors were saying ‘Well, Mute Records is a nice little label but they won’t get you any international success,’ and they offered them quite significant deals.

- Read more: Pop Art – Vince Clarke

“I remember one guy, a young A&R guy for London Records or Polydor, and he was really pestering them. He thought that the band agreed to sign with him, so we had this lunch with [the label boss] Roger Ames.

Vince and Dave were there and the first thing Roger said was ‘Great news, we’re going to be working together.’ Vince just said ‘No’ – one word – and that was the beginning of the lunch! A lot of people were interested in signing them, but with amazing credit to them, they were loyal and said ‘Yeah, let’s do it this way.’”

Power of one

Never one to choose the obvious route, however, Vince famously departed Depeche just as they were approaching the first of many peaks. “It was a shock but not [a surprise],” Daniel states. “We did a tour of Europe – I was driving the van, doing the sound, tour managing.

“I didn’t even know the band that well then, but I noticed that Vince had become distant. He would sit in the front with me and the others would be in the back larking around and he would just be very quiet.

“The other thing was when he played the band a rough version of I Just Can’t Get Enough. They really didn’t want to do it because they thought it was too poppy, so I think there was already a bit of a musical difference – not big, but an undercurrent. So when he decided to leave, I guess it was a shock but I had felt something wasn’t quite right.”

Another deciding factor could well have been Vince’s early fascination with the technology of the time. “He was really hungry to learn about synthesizers and everything about the studio,” Daniel says.

“One of the reasons that maybe pushed him over the edge to leave Depeche – and I think that he has said this as well – was the digital sequencer, the Roland MC-4, which he really embraced and quickly figured it out. He thought ‘Hang on a second, I don’t need a band now, I can do it with this.’

“I think he found the band – not in any way the individual members – but the concept of having to agree on everything with three other people who might have different ideas to him, I think he found that challenging. He’s not a confrontational person.”

As the major writer in Depeche, though, was it perhaps obvious that Clarke would stay with Mute Records for further pop success? “Well, it wasn’t inevitable,” Miller considers, “but very soon after that he came to me with Only You. I understood it as a great pop song but I wasn’t sure on the very first listen as to whether I liked it or not.

“I was kind of distracted as I was trying to do something else – I’m always distracted when these moments happen [laughs]! But of course we ended up working on it and it was a brilliant project.”

Only You, initially meant as a one-off single, “became a massive hit, again very quickly”– and the resulting Yazoo partnership that Clarke formed with Alison Moyet flourished with two albums, Upstairs at Eric’s and You And Me Both. But success arrived possibly too quickly this time.

“Vince had already been there but it thrust Alison into this world that she [didn’t know],” Daniel explains. “She was basically a blues singer and I don’t think she even particularly liked electronic music. Very quickly it exploded and we were travelling around Europe and going to America.

“They didn’t have a particularly strong relationship before; they just knew each other from school. Of course it was exciting, but I think it also took a toll on both of them.

“Alison Moyet was not a conventional frontwoman in the early 80s – there was a kind of stereotype front person and she wasn’t that and there was pressure on her. They were young people plucked out of housing estates in Essex and put into this other world.

“Clearly, by the second album, they weren’t really talking to each other,” he continues. “I don’t know if that came from Vince or from Alison, but they were never in the studio at the same time.

“They didn’t really want to make that second album so I said ‘Look guys, I don’t want to force you but this is an amazing opportunity to build on this great success, so think about it.’ They did it anyway, but they’d already fallen out before we started making it.”

Having bounced back from Depeche to Yazoo, Vince almost inevitably then went on to find huge success with another collaborator, Feargal Sharkey, for the hit Never Never, this time as part of The Assembly.

- Read more: Erasure interview

It was a pairing that was part of a bigger plan by Vince and engineer/producer Eric Radcliffe (”a very important part of that whole few years of Depeche and Yazoo”) to team up with a variety of different singers – a plan that ultimately didn’t materialise.

“Vince wasn’t sure what to do after that,” says Miller, “but at some point he said ‘I’m going to start a new project,’ and that’s how eventually Andy [Bell] got on board. That story is well-told: I think Flood and Vince did 40 auditions and nothing really happened and Andy was the last one.”

Slow burn

After three incredibly-bright but short-lived projects, Vince’s most enduring musical partnership with Andy Bell as Erasure would ironically start with less success.

“They made the first record [Wonderland] with Flood and it didn’t connect with people,” Daniel recalls. “By this point the music on the radio had changed. It was much more rock-orientated, and when you’re playing Bruce Springsteen and Van Halen – God rest his soul – Erasure didn’t really fit the picture.

“Oh L’Amour was a huge hit in France, which was a good thing, but we tried all sorts of things – different songs, different mixes – and nothing really connected. All credit to Vince and Andy, though, they went out on the road in the back of a Transit and did college gigs and half sold-out concerts. They worked like a new band, and the gigs were great.

- Read more: The story of Mute

“And then one thing really turned it round,” he continues. “We had a studio on the top floor of the Rough Trade building in Kings Cross, just a makeshift studio, and I remember Flood or Vince phoning me and saying ‘Hey, I think we might have cracked it,’ so I said ‘Great, I’ll come over.’

“I did, they pressed play and left the room, and I heard Sometimes and I thought ‘F***ing hell, this is amazing.’ It had everything that was maybe missing on the album.

“It wasn’t called Sometimes then – it had the same melody but I think it went ‘Ooh baby’. But we thought it was amazing and approached Laurie Latham, a very good producer and mixer, and he did a good mix – but not the right mix.

“He said ‘I’m not sure about that lyric,’ so we rejected the mix but I said to Vince ‘What do you think about that [lyric change]?’ so he said ‘Yeah, alright, let’s have a look,’ and they changed it to ‘sometimes’.

“Flood then mixed it and we knew there was so much hanging on this being right, so we spent hours, maybe days mixing it.”

Sometimes would ultimately bring Vince the kind of success he had become used to, but there are parts of that success that he has never seemed comfortable with. “He hates being in the public eye apart from when he’s playing,” Miller agrees. “He’s still very shy, so for some people it takes a long time to get to know him.”

And after four decades having got to know Vince Clarke better than most, how does Daniel sum him up?

“Unbelievably down to earth; tells occasionally good jokes, but often terrible ones; seems relatively unaffected in a negative way by all the success he’s had; and is a warm, friendly guy who you can talk to about everything. He’s just a warm-hearted, brilliant musician and songwriter.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!