Reintroducing the hardline according to Sananda Maitreya

By Classic Pop | December 3, 2022

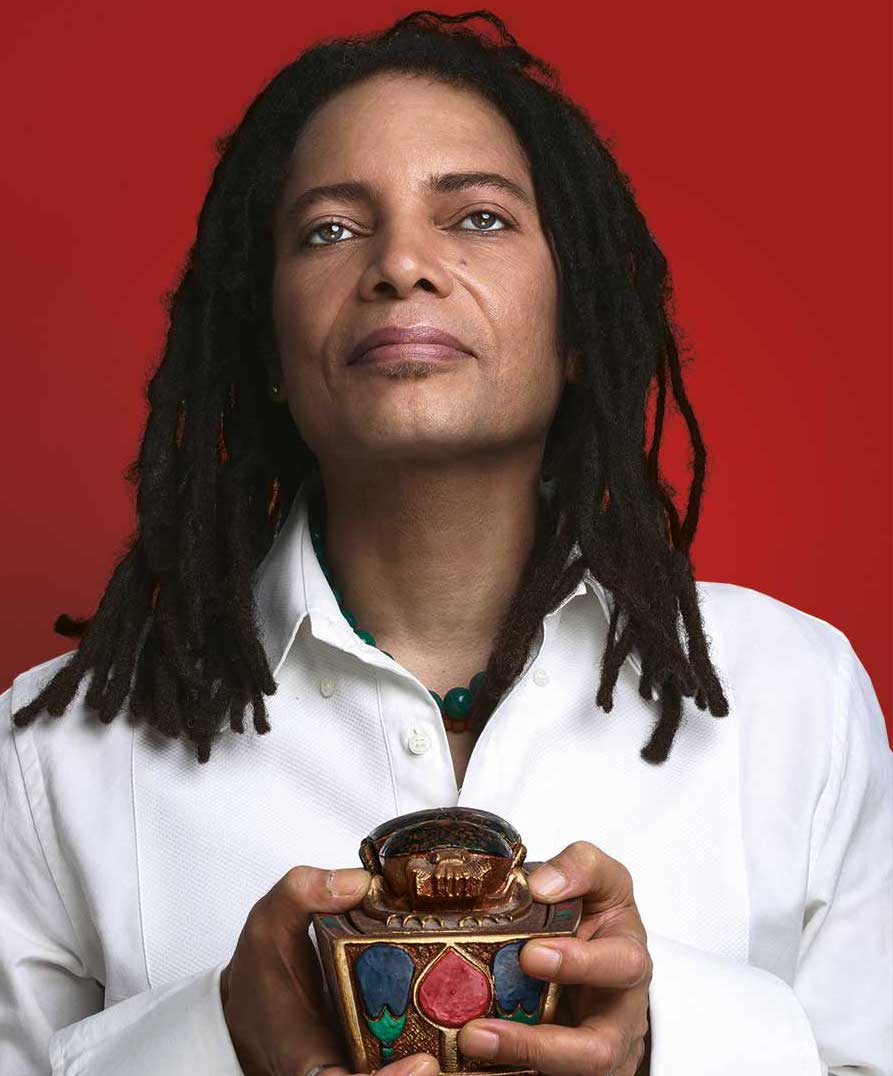

In 2017, we caught up with Sananda Maitreya – otherwise known as The Artist Formerly Known As Terence Trent D’Arby – to talk culture wars, name changes, Greek myths and Angelina Jolie… By John Drake

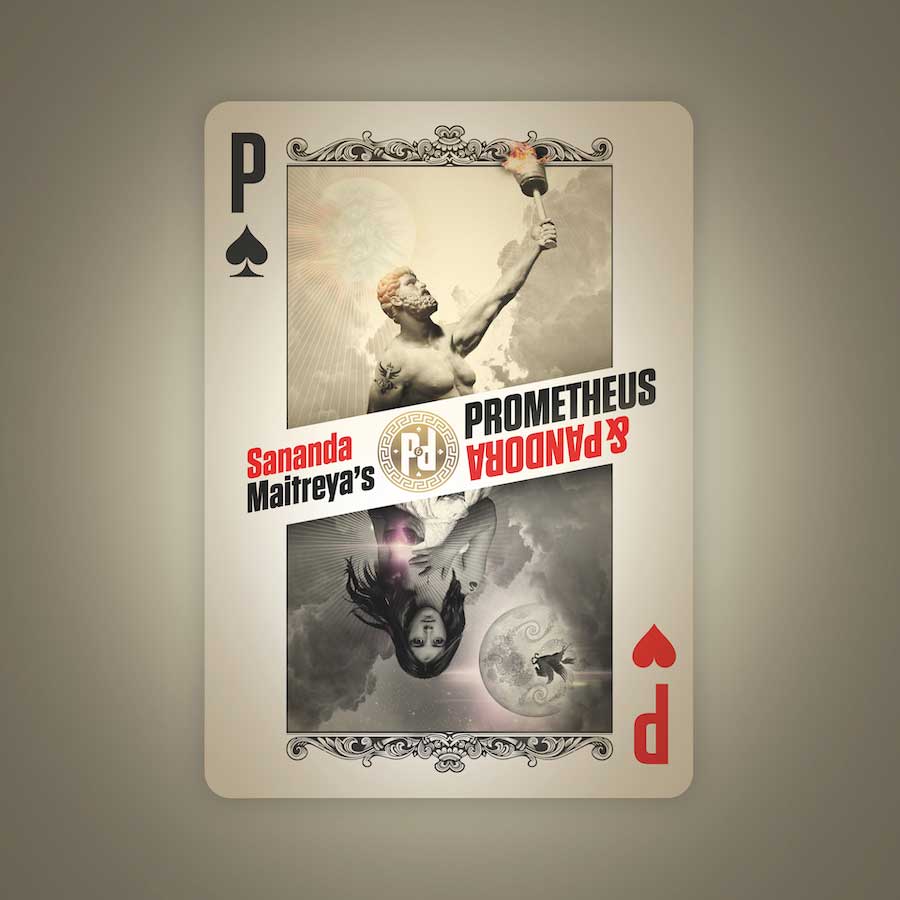

Classic Pop has been with Sananda Maitreya — a musician you might know better as Terence Trent D’Arby, the 80s pop-soul polymath widely feted for his songs and his rampant self-belief — for 10 minutes and already he has held forth on subjects as varied as self-driving cars, the North Korean missile crisis, the “culture wars” of the punk era, and the contemporary relevance of assorted Greek myths and legends: his latest album as Maitreya is titled Prometheus & Pandora.

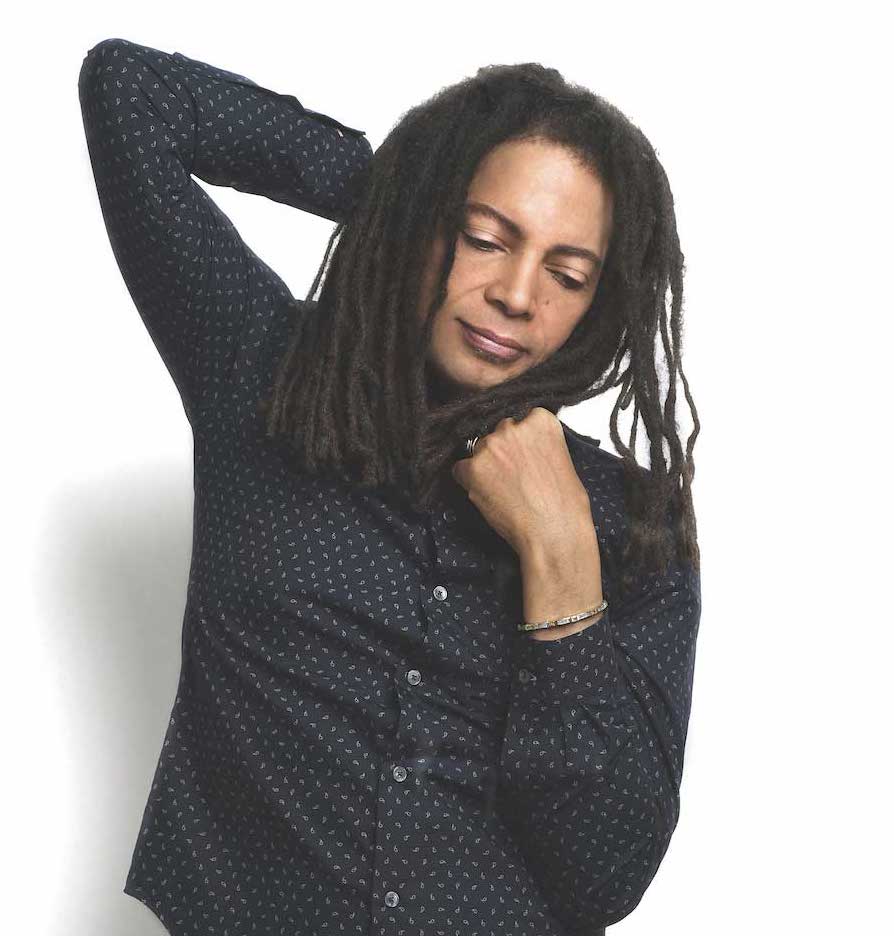

We are sitting on the upper terrace of a friend’s home in central Milan — he confides that he was uncomfortable about me seeing his own apartment because it’s so untidy — where it is intensely bright and hot.

Shades on, hardly making eye contact, instead staring vaguely towards the sky, he has barely paused for breath. It’s as though he believes, if he keeps talking, he can dictate the direction and content of the interview.

To try to turn it from a manic monologue into a calmer conversation, I finally manage to interject with an, “Anyway, how are you?” The question seems to stop him in his tracks. “I’m hanging on in there,” he says, suddenly weary. “Thanks for coming, by the way.”

Maitreya — he and his team have asked if this can be trailed as a Sananda Maitreya feature, not a Terence Trent D’Arby one — has been through the mill, and then some.

The net result has been a name change, a shedding of his old skin, and a rebirth. Classic Pop is politely requested not to refer to him as TTD, not through folly, but because it causes him anguish. You can see it when he talks about the past: he visibly winces.

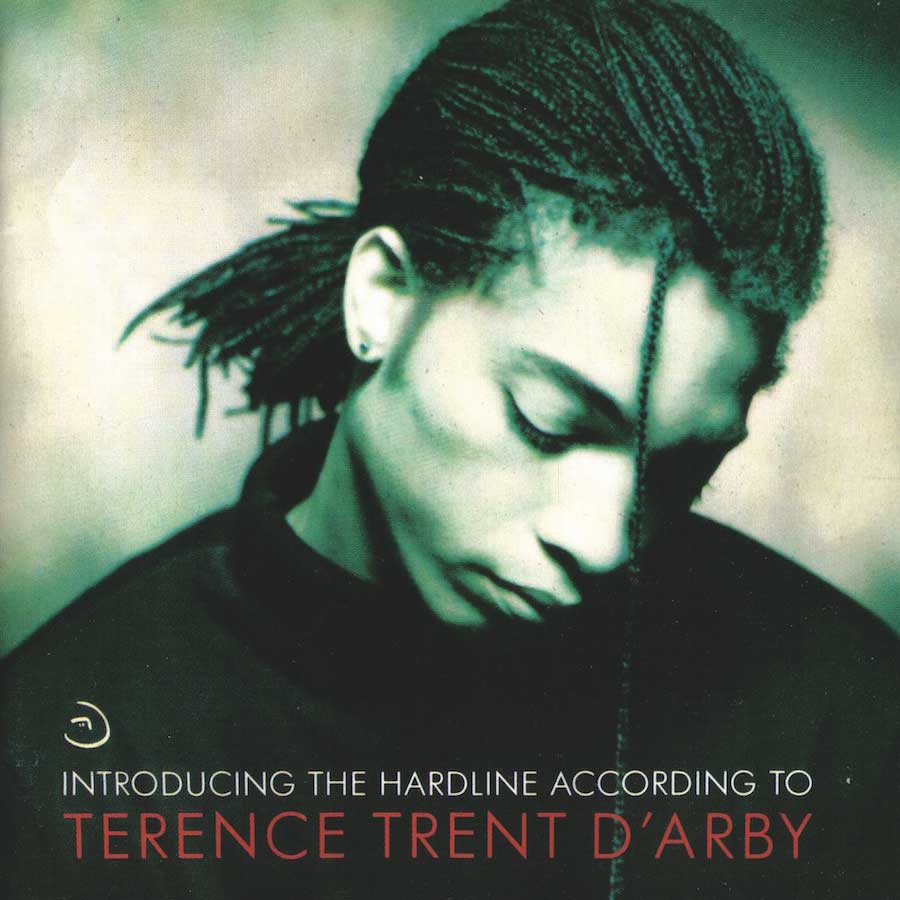

He has been living in Milan for 15 years, with his wife and two young sons. The US-born performer came to Italy after two long sojourns: the first, in London, where he launched his career in 1987 with nine million-selling debut album Introducing The Hardline According To Terence Trent D’Arby; the second in Los Angeles, where he moved after the crushing failure of follow-up Neither Fish Nor Flesh (1989), and his subsequent mental deterioration.

He is happy here, he says, as his wife trains a camera on us (she is recording our encounter), then prepares some lunch for us all.

“This is the heart of Milan,” he announces. “When you’re in the heart of a city, it’s a great place to be. These European cities had a level of understanding of mathematics and science…”

Releasing four albums as D’Arby (Introducing, Neither Fish…, Symphony Or Damn in 1993 and Vibrator in 1995), he officially changed his name in 2001 and has issued eight more, albeit somewhat below the radar compared to his heyday. These include two volumes of Angels & Vampires in 2005-06 and 2009’s Nigor Mortis.

The most recent three albums have all been epics in terms of subject matter, size and scope: the 22-track Return To Zooathlon (2013) and double album The Rise Of The Zugebrian Time Lords (2015), on both of which he created self-contained fictional universes.

On his latest, Prometheus & Pandora, a 53-track, 178-minute triple, he muses on matters existential through the prism of Greek mythology.

The titles might seem arcane, but the music is still an engaging mix of Beatlesque pop, hard rock, soft soul, 60s psych and 70s funk, with some cool jazz thrown in for good measure.

“Mind you,” he says of the latter mammoth triple-LP, which he describes, with some of the hubris of yore, as Wagnerian and the final part of a trilogy in his Post Millennium Rock Phase, “it took its toll. I’ve never been as exhausted on every single level as I was after this project. In fact, I’m still recovering.”

Artistry over commerce

In a way, he has been recovering for nearly 30 years. The debut album — and its attendant singles, If You Let Me Stay, Wishing Well, Dance Little Sister and Sign Your Name — made D’Arby, a former army recruit and boxer, the toast of the UK, and a star almost of the magnitude of his closest rivals, Prince, Michael Jackson and George Michael. He had everything: vocal prowess, songwriting smarts, and pulchritude.

For two years, he had hits and won awards. But his first misstep was to not make, with Neither Fish Nor Flesh, a copycat version of Introducing The Hardline… It was, instead, lambasted for its pretensions and muddled material. As Maitreya accepts, he swaggered into town, and dared to fly too close to the sun, putting artistry above commerce.

Did he conceive of Neither Fish… as his magnum opus?

“I didn’t see it as a magnum opus, I saw it as the next logical step,” he argues. “I wasn’t trying to make money and be famous. I’m – dirty word – an artist. Art gave me life.

“I was,” he continues, “offensive to some people. Like, ‘Who does that guy think he is?’ They wanted me to be the nice polite black kid. But really I was just a clown trying to draw attention to the work.”

- Read more: Remembering The Tube

He quotes John Lennon, one of his heroes. “One of my favourite songs is Julia from The White Album, where he sings: ’Half of what I say is meaningless/But I say it just to reach you.’ He was a provocateur, just as I was.”

He has talked before about his “death” following the fallout from Neither Fish…, when he would have been 27 and a putative member of “that stupid club” — meaning, he died inside, killed by the mean-spirited nature of the critical opprobrium.

On other occasions, he has identified the moment of his demise as 1995, when he was 33, the age Jesus was when he died — Maitreya frames his breakdown in terms of crucifixion.

He was, he insists, harried to the point of annihilation by record companies. When confronted or questioned with even a hint of scepticism about this, he gets impatient.

“What is so hard to understand? Everything is staged and scripted,” he says. His psychic collapse necessitated a resurrection of sorts. But this wasn’t a Bowie-style ch-ch-ch change. It was a wholesale physiological regeneration.

“It was beyond cellular,” he confirms with a heavy sigh.

He says he was “always Sananda Maitreya” and he was assigned “the role of this other form” (i.e. Terence Trent D’Arby), which he performed “until they [outside forces/record companies] pulled the plug on that role. They didn’t pull the plug on Sananda; they pulled the plug on that particular script and psyche.”

Vehicle for the zeitgeist

Talking of scripts… His life would make a great movie. This isn’t the first time the subject has come up.

“I’ve already got directors wanting to do my story,” he tells me. “Because it’s so fuckin’ dramatic. You don’t have to make this shit up. It’s like Master Shakespeare said: we’re all just players.’”

So who would play him? Of course, he was never going to say anyone predictable.

“Angelina Jolie,” he proposes. “I love that idea, like when Joseph Fiennes played Michael [in an episode of comedy show Urban Myths that was pulled due to complaints from Jackson’s daughter Paris] or Cate [Blanchett] played Dylan [in 2007’s I’m Not There]. “I kind of see two films eventually,” it suddenly occurs to him.

“Let’s have an actor who doesn’t look like me and see how it plays out. Or a chick. It’s a story that has to be played out. I’m just a vehicle for the zeitgeist — all artists who are breaking their heart are.”

He says he was “designed to be a whipping boy” for the press, although to be fair he was garlanded with praise for a while. Mouthy and opinionated, he was a gift to the media: one music journalist wrote early on that D’Arby was, “like something invented by three rock critics on the ’phone”.

A former trainee journalist himself, he knew the power of the eye-catching pullout quote, and he enjoyed sparring with the British music press.

Maitreya as D’Arby was a paradox: at once iconoclastic and reverential, keen to pay homage to his heroes, whether Hendrix or Wilson Pickett. He was part of a continuum, not a break with tradition. He sees this, as he does many things, as a racial issue.

“For me, it was important to establish there was a new blade in the guillotine, but I was part of a continuum,” he agrees. “Master [John] Lydon had to play that role [of the radical], storming the Bastille.

“You’ve got to be careful putting a black guy in that role — they see him coming a mile off. You’ve got to come subtle, bobbing and weaving. You can come out and be bold and bombastic like I did — but then you get crucified.”

He was crucified, he believes, for refusing to be reduced to an R&B role when he had far more wide-ranging ambitions than that.

“I think of myself as a jazz or classical artist,” he declares. “The record company didn’t like that. ‘What the fuck are we gonna do with this kid?’ The Americans told me: ‘All you’ve got to do is make a Sam Cooke record and we’ll give you the world.’ But what makes you think, just because he’s one of my gods, I’m trying to be him? I want to go past him.”

- Read more: The Lowdown – Michael Jackson

Furthermore, he is convinced Cooke and Otis Redding were killed off because their later work took a turn for the political.

“The hero factory is serious business,” he decides. “They control fucking consciousness!”

A police siren wails on the street below as Maitreya depicts the music industry as a vale of tears controlled by discreetly murderous forces capable of bumping off artists who get out of line. Michael Jackson, Prince and George Michael all had run-ins with their labels. Is he implying they were killed?

“I don’t want to, in this click-heavy age, say,” he ventures, hesitantly for once. “But let’s just say their services were withdrawn from Babylon. Let me ask you: is it a coincidence they all died relatively young, and also spent significant amounts of time opposing the industry?

“Even if they weren’t killed,” he allows, “it kills you, brother: the struggle. I’ve survived the beatings – I’m a big boy – but artists are incredibly sensitive bitches. Even if there wasn’t a deliberate plan to kill Prince, the struggle killed him.

“Your heart gives up. Same as Master George [Michael]: he took on a major record company, and he tried to absorb that. But he was targeted. Otherwise he’d have been protected like fuck!”

Far be it from Classic Pop to suggest Maitreya is a conspiracy theorist, but he even accuses the powers that be of hounding Janis Joplin for not wearing make-up.

“One reason she didn’t have a long life is because she changed the way chicks saw themselves. She was like, ‘Fuck all this lipstick!’ So when you’re a pharmaceutical industry like L’Oreal and you’ve got an icon like Janis, a blues singer who white girls look up to, and she doesn’t wear that shit…”

So Janis was killed for not wearing blusher? “I didn’t say she was killed. She was a volatile person in a volatile time. The shit killed her. She was marked.”

Was Maitreya marked?

“I still am!” he proclaims. “I’ve just learned how to deal with it. I’m one of the most heavily targeted and surveilled bitches in the situation. We all know this.”

Is his phone tapped? “I’m kept an eye on,” he says. “Occasionally they send signals to let you know they’re omnipotent…”

There follows a five-minute disquisition on NASA and the military-industrial complex as he paints a picture of a world like something out of Orwell’s 1984 via The Truman Show (the latter one of his favourite films). Would he describe himself as paranoid?

“Well, paranoia is a useful tool,” he replies. “As the saying goes, just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean the police haven’t been following you for a while. Often, people are accused of being paranoid when they just have a heightened sense of awareness of their surroundings. The easiest thing is to blemish them as paranoid.”

Restating his case

Over the next few days, Maitreya sends me a series of emails, demonstrating that, far from paranoid, he is merely sensitive and concerned, understandably given that this is his first major British press interview for years, to present himself in a favourable light.

“I even think I might have bumped into LEWIS CARROLL when hurtling at great speeds through the trajectory of the rabbit hole,” he writes, using capitals for dramatic effect.

“I fell so quickly into that it felt like going back to the womb. IF THE WOMB BELONGED TO A WOMAN. In An Earthquake. ALSO ON A ROLLER COASTER scaring the shit out of the screams of everyone on it.”

Elsewhere, he dismisses claims he’s attempting a return to the fray with his new LP (“WHY THE FUCK WOULD I WANT TO RETURN TO MY OWN GRAVEYARD?”), although he acknowledges the paradox that is recording an album and wanting it to reach as wide an audience as possible while being careful not to succumb to fame and its all-consuming potential.

“Dude,” he writes in his second lengthy email, “success is this: I am alive still, I’ve left a body of work that I can claim with a measure of pride, I have a wonderful family, a new generation or 2 of friends, AND MUCH LESS BULLSHIT to deal with in pursuing my craft save the ‘Empire Games’ with which sometimes I must deal.

“There is always a price to pay for moving on, a toll. So I pay it & continue on my way. Most of us after a certain number of years’ experience in the rabbit hole understand CLEARLY that almost ALL OF THIS IS AN UNAVOIDABLE PARADOX.

“But you buckle down accompanied by love & your best medicinals, your favourite herbals AND YOU GET ON WITH IT.

“And once again,” he continues, “IF TO REPEAT THE LAST EXPERIENCE WAS WHAT I WAS LOOKING FOR, WHY ON GOD’S GOLDEN GREEN WOULD I BE TALKING TO YOU NOW FROM YOUR PRESUMPTIONS?

“THAT TRAGIC LIFE WAS DEATH, pure hell & death rolled into one nice stimulus package,” he concludes.

“There can simply be no other plausible reason why a relatively sane person raised with capitalist sensibility just WALKS AWAY from a burning wreckage unless it were felt to be unsalvageable. Period, end of story.”

Back in Milan, Classic Pop prepares to say goodbye to Maitreya and his wife. I hope the interview wasn’t too gruelling, I say. “No, I kind of needed it,” he says, smiling. “I don’t do this often. It’s psychologically helpful.”

And Maitreya’s return with the grandly mythological Prometheus & Pandora has a rival benefit. Pop music needs musicians with his wit and vision.

“I just don’t think anybody should apologise for not thinking small,” he asserts. “What did all my heroes write about? What did Mozart and Wagner write about? Stories about people, but rewritten. We live in a time of such fear, such trepidation. Being an artist and writing from the heart takes audacity.

“I try to stay under my own spell,” he adds. “With all due respect, I’m never going to let how you see me dominate how I see me. That doesn’t make sense — slaves do that.”

He may have been through hell, but reborn he’s no simpering Buddha. In fact, he has a final word of advice. “Just,” he warns as I climb into the taxi to the airport, “don’t make me look like an idiot.”

Job, hopefully, done.

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!